Serval Cats

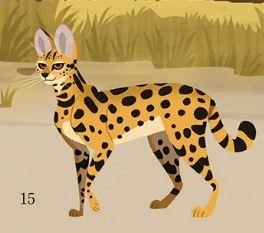

Serval Cats are medium-sized African wild cats. The Serval Cat is mated with a domestic cat to produce a hybrid cat breed called the Savannah Cat. They have long and slender bodies, with distinctive ears and legs (Markula et al., 2009). They have the longest legs and biggest ears in relation to body size for any cat species (Livingston, 2009). The backs of their ears are black with noticeable central white bars (Ocile). They also have small heads, elongated necks, long slender bodies, and short tails.

© F1Hybrids Savannah Cats | Serval Cat Information

Their coat color is a yellowish tan (almost a butter yellow) with black spots, bands, and stripes, which are unique to each individual. Serval Cats can jump straight up 7ft into the air in a single bound. They have short tails that have black spots and rings (Markula et al., 2009). Servals with black coats have been reported, as well as rare sightings of white Servals (IUCN, 1996). Males are bigger than females (San Diego Zoo, 2010).

The serval is a carnivore that preys on rodents, particularly vlei rats, small birds, frogs, insects, and reptiles, and also feeds on grass that can facilitate digestion or act as an emetic. Up to 90% of the preyed animals weigh less than 200 grams (7 oz).

With its large ears the Serval uses echolocation to detect prey hidden in the grasses. Then using their long legs and incredible jumping power Servals can leap vertically up to three meters to catch birds flushed from the grasses.

Genetically the serval (Leptailurus serval) is closely related to the African golden cat (Caracal aurata) and the caracal (Caracal caracal). No recent morphological and molecular studies have been conducted

Leptailurus serval serval in southern Africa

Leptailurus serval constantina in West and Central Africa and

Leptailurus serval lipostictus in East Africa

Distribution of Leptailurus serval (Breitenmoser-Wursten et al., 2008). © REDLIST

Habitat

Serval Cats are found in sub-Saharan Africa, distributed from Senegal and Guinea in the west to Ethiopia and southern Somalia in the east and south to Angola, Zimbabwe, and Mozambique (Breitbeil, 2002) (See Figure 1).

There is the possibility have been reported that Servals are also found north of the Sahara in Morocco and possibly northern Algeria. (Breitenmoser-Wursten et al., 2008).[TJ1]

Servals were also once found in Tunisia but went extinct however a population has been reintroduced into Feijda National Park (Breitenmoser-Wurstenetal.,2008).

Tropical grasslands include the hot savannahs of sub-Saharan Africa and northern Australia. Rainfall can vary across grasslands from season to season and year to year, ranging from 10 to 40 inches annually.

Temperatures can go below freezing in temperate grasslands to above 90 degrees Fahrenheit.

Diet

Servals are strict carnivores (Mellen & Wildt, 1998), however, there have been various accounts of them consuming vegetation in the wild (Breitbeil, 2002). They are specialized rodent hunters, rats being the dominant rodent they catch followed by mice (IUCN, 1996).

They are also excellent jumpers, extending their prey capture to birds and insects (Livingston, 2009). In addition to rodents, birds and insects they will also eat reptiles and amphibians (IUCN, 1996). A scat analysis of a wild population showed they have a diet consisting of 60% rat, 15% mice, 5.6% birds and small amount of insects and reptiles (Markula et al., 2009). They are capable of hunting and capturing larger prey such as small antelope, rabbits (Markula et al., 2009) and flamingos (Livingston, 2009).

The Serval is an opportunistic predator and being that most of their prey is small in size they hunt frequently. It has been estimated that an adult Serval will spend 6 hours hunting and travelling in a 24 hour period, making several kills in that time (Markula et al., 2009). They have a high prey catch success rate of 48%, one of the highest of Felidae species (Livingston, 2009).

Their long legs and big ears provide various hunting techniques. Servals can be patient hunters using their excellent hearing to pinpoint the exact location of their prey, whether it’s moving through long grass or underground. Their long legs not only provide an advantage on land but also in water and getting up into the air. They are known to hunt in shallow waters for frogs, fish and water birds (Sunquist & Sunquist, 2002). On land they can dig, use their long arms down animal burrows, zigzag bound through grass and pounce on prey.

They use the force of their forearms to strike their prey when pouncing on it. Their legs also propel them into the air, being able to leap horizontally 1-4m and vertically 3.5m, allowing them to catch insects and birds mid-flight (Markula et al., 2009). They have been seen clawing at the prey in flight or slapping them between their front paws (Livingston, 2009).

Behavior

Servals are solitary animals, only coming together when the female is in oestrus (Breitbeil, 2002). Male and female have their own territories, with the male territory being bigger and overlapping into several female territories (Markula et al., 2009,, San Diego Zoo, 2010).

Territories are marked with urine sprays and faeces, (San Diego Zoo, 2010), with males marking at least twice as much as females (Sunquist & Sunquist, 2002). It has been estimated that the density of Servals in an area is one to every 2.4 kilometres. Females show strong site fidelity, occupying the same territory for many years (Sunquist & Sunquist, 2002).

Servals are mostly crepuscular and nocturnal but are also known to be active during the day (Breitbeil, 2002), which one may attribute to human presence and larger predators’ times of activity (San Diego Zoo, 2010). Servals tend to be inactive for at least 40% of the day, usually during the hottest part of the day (San Diego Zoo, 2010). When active they can cover as much as 3-6 kilometres in one night (Sunquist & Sunquist, 2002).

Reproduction

Male and female Servals will come together during a female oestrus, which happens several times a year and each oestrus can last 1-4 days. The pair will sometimes travel and rest together during the female’s oestrus (Sunquist & Sunquist, 2002). Females can give birth twice a year, with a minimum interval of 184 days. Gestation in the wild is estimated at 66-77 days, with an average litter size of 2-3 kittens (Markula et al., 2009). The month they give birth is usually before peak rodent reproduction (Wilson & Mittermeier, 2009) but fall in different months in the various locations in Africa (Sunquist & Sunquist, 2002). Birthing dens are hidden in dense vegetation or disused Aardvark or Porcupine burrows (Wilson & Mittermeier, 2009).

Pattern

There are two different spot patterns for servals. In the more generally known pattern, the tawny-colored fur is covered with large black spots. The lesser-known serval fur pattern is called “Servaline” where a lighter-colored fur is covered with faint, speckled spotting. Instead of the absence of dark tabby markings, the markings have increased in number and decreased in size to the extent that they are hardly noticable.

Spotted Pattern (Pictured on left)

Servaline Pattern (Pictured on right)

Melanism

Melanism, a development of the dark-colored pigment melanin in the skin or its appendages, has been described in many species globally. In cats (Felidae) it is well-documented in leopards (Panthera pardus), and to a lesser degree Jaguars, Ocelots and other smaller cats. The reasons for the prominence of melanism in cats are not well understood. However, several theories posit that melanism is particularly relevant in high-altitude areas and forests, where cats are likely to be less exposed to open sunlight.

Manja — the melanistic serval first spotted at Namiri Plains in 2019 by Asilia guide and naturalist of the same name — and his mate have produced melanistic serval kittens.

wildlife photographer Will Burrard-Lucas

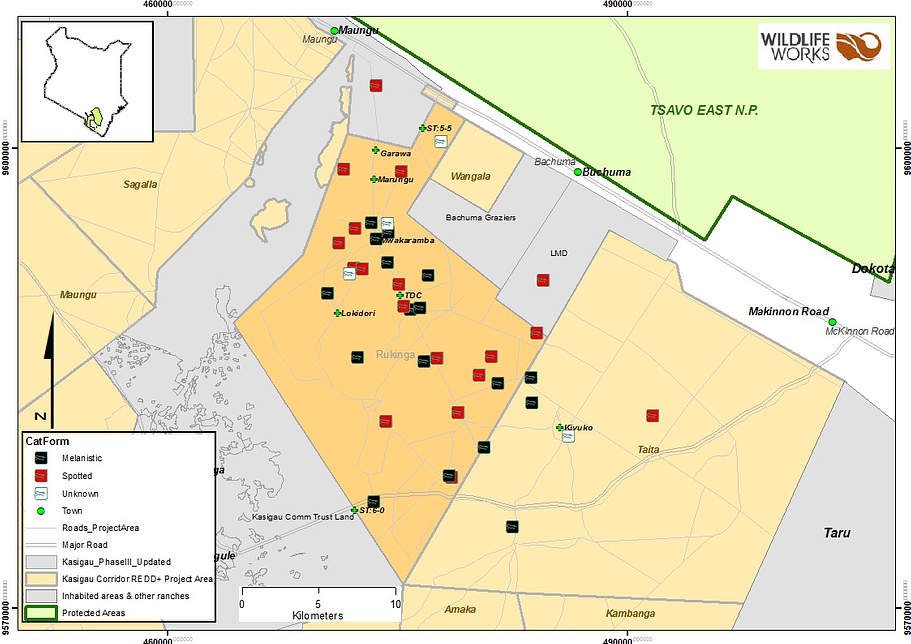

Serval sightings recorded in the Tsavo ecosystem.

Map 1 (above) - Serval sightings recorded in the Tsavo ecosystem.

Map 2 (below) - Serval sightings recorded in Rukinga - Taita area (within Tsavo ecosystem). Wildlife Works compiled the data on serval sightings in the Tsavo Ecosystem.

Serval sightings recorded in Rukinga - Taita area (within Tsavo ecosystem). Wildlife Works compiled the data on serval sightings in the Tsavo Ecosystem.

Population Status

[TJ1]According to IUCN there have been reports from Morocco (and under wild populations you’ve said there are fewer than 250 mature animals there) Might also be good to mention they have bee reintroduced to Tunisia and that they are believed to be extinct in Algeria.

The IUCN red list lists Servals as “Least Concern” as they are relatively abundant and widespread in their range and have a stable population trend (Breitenmoser-Wursten et al., 2008). It is estimated that there are at least 50,000 individuals in the wild (WAZA, 2012). However the isolated population north of the Sahara in Morocco is classified Critically Endangered for that region. It is estimated that there are fewer than 250 mature individuals in that population (Breitenmoser-Wursten et al., 2008).

High carnivore population density highlights the conservation value of industrialized sites. Camera trap image of a serval at the heavily industrialized Secunda Synfuels Operations plant in South Africa, recorded by Reconyx Hyperfire HC600 camera.

The Serval is protected under CITES (Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species) Appendix II, however national legislation does not provide protection over most of its range. The Serval is under Appendix II on CITES because this species “is not necessarily now threatened with extinction but that may become so unless trade is closely controlled.” An export permit or re-export permit is required for international trade of this species (UNEP-WCMC, 2012).

Hunting is prohibited in Algeria, Botswana, Congo, Kenya, Liberia, Mozambique, Nigeria, Rwanda, South Africa (Cape Province only). Hunting is regulated in Angola, Burkina Faso, Cental African Republic, Ghana, Malawi, Senegal, Sierra Leone, Somalia, Tanzania, Togo, Zaire and Zambia. There is no legal protection in Benin, Cameroon, Ethiopia, Gabon, Gambia, Guinea Bissau, Ivory Coast, Lesotho, Malawi, Mauritania, Morocco, Namibia, Niger, South Africa, Sudan, Swaziland, Tunisia, Uganda and Zimbabwe (IUCN, 1996).

A key threat to the Serval is the degradation and loss of the wetland habitat. Their main food source, rodents, is in high densities in wetland habitats in comparison to other habitats. Also burning of grassland habitats can reduce Serval prey as well (IUCN, 1996). Other threats include capture for their pelts and use of body parts in traditional medicines (Breitenmoser-Wursten et al., 2008).

Captivity

Servals are raised in captivity. Out of all exotic felines kept in captivity, they are notably more driven for human interaction but not without several drawbacks. Serval cats will not entirely use a litter-box. They also are singular animals with deep bonds with only one given caretaker, they strongly dislike strangers and will be driven to flee away. Servals hit emotional maturity at ~3 years old, this is when their youthful personality will reveal the true exotic nature of the adult feline become distinctly independent.

Kid Education

PBS Kids, Wild Kratts Video

REFERENCES

Husbandry for Leptailurus serval (September 2012)

Arliah Hayward (Mammals Keeper, Carnivores)

Adelaide Zoo, Adelaide, Australia

zoossa.com.au

Andrews, P. (2003) Hand-rearing of small felids. Hexagon Farm Wild Feline Breeding Facility.

Breitbeil, B. (2002) Serval, Leptailurus serval. North American Regional Studbook 1st Ed. FL, USA.

Breitenmoser-Wursten, C., Henschel, P. & Sogbohossou, E. 2008. Leptailurus serval. In: IUCN 2011. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2011.1. <www.iucnredlist.org>. Downloaded on 02 October 2011

Crissey, S.D., Slifka, K.A., Shumway, P. & Spencer, S.B. (2001) Handling Frozen/Thawed Meat and Prey Items Fed to Captive Exotic Animals. A Manual of Standard Operating Procedures. United States Department of Agriculture (USDA).

Daily Mail (2008) “Shakira the Serval kitten finds puppy love in her adoptive home…with a pack of Rhodesian Ridgebacks” <www.dailymail.co.uk> > Dowloaded on 19 September 2012

Department of Agriculture, Fisheries & Forestry (DAFF) (2009) Draft Australian Animal Welfare Standards & Guidelines: exhibited animals. DAFF Animal Welfare Branch <www.daff.goc.au/_data/assets/pdf_file/0006/762846/draft-animal-exhibit-standards.pdf

Goodrowe, K.L. (1992) Feline reproduction and artificial breeding technologies. Animal Reproduction Science 28: 389-397

Hedburg, G.E. (2002) Exotic Felids. IN: Gage, L. (ed.) Hand-rearing wild and domestic mammals. Ames, Iowa State Press, USA. Pgs. 207-220.

Hosey, G., Melfi, V. & Pankhurst, S. (2009) Zoo animals: behaviour, management and welfare. OUP Oxford, UK

Howe, A. (2011) Carnivore vaccinations at Monarto Zoo. University of Sydney. Unpublished research paper.

IATA (2007) Live Animals Regulations. International Animal Transport Association. Montreal, Quebec

IATA (2013) Live Animals Regulations. International Animal Transport Association. Montreal, Quebec

International Species Information System, ISIS (2014) Weight comparison report- Serval. <https://zims.isis.org> downloaded on 26 February 2014

IUCN (1996) Sub-Saharan Africa Species Accounts: Serval, Leptailurus serval. IUCN/SSC Cat Specialist Group <http://www.catsg.org/catsgportal/cat-website/catfolk/serval01.htm> downloaded on 01 May 2012

Kasa (2002) Reproduction bio-technologies in the conservation of wild animal species< www.kasa.org.br/projectoeliasing.doc> downloaded on 03 September 2012

Livingston, S.E. (2009) The nutrition and natural history of the Serval (Felis serval) and Caracal (Caracal caracal). Vet Clin Exot Anim 12: 327-334

Lopate, C. (2012) Management of pregnant and neonatal dogs, cats and exotic pets. Wiley & Blackwell, USA

Markula, A., Hannan-Jones, M. & Csurhes, S. (2009) Pest animal risk assessment: Serval, Leptailurus serval. Invasive Plants and Animals, Biosecurity Queensland, Department of Primary Industries and Fisheries, Brisbane, QLD.

McLelland, D. (2012) Preventative Medicine Program, Serval. Adelaide Zoo

Mellen, J.D. (1991) Factors influencing reproductive success in small captive exotic felids (Felis spp): a multiple regression analysis. Zoo Biology 10: 95-110

Mellen, J.D. (1992) Effects of early rearing experience on subsequent adult sexual behaviour using domestic cats (Felis catus) as a model for exotic small felids. Zoo Biology 11: 17-3

Mellen, J.D. (1993) A comparative analysis of scent-marking, social and reproductive behaviour in 20 species of small cats (Felis sp). American Zoologist, 33: No. 2, 151-166

Mellen, J.D. (1997) Minimum Husbandry Guidelines for Mammals: Small Felids. American Association of Zoos and Aquariums (AZA)

Mellen, J.D. & Wildt, D. (1998) AZA small felid husbandry manual. American Association of Zoos and Aquariums (AZA)

NSW Department of Primary Industries (NSW DPI) (2005) Standards for Exhibiting Carnivores in New South Wales. Exhibited Animals Protection Act 1986, NSW Department of Primary Industries. NSW, AU.

Robbins, A. (2011) Annual report for Serval. Species coordinator. Auckland Zoo

San Diego Zoo (2010) Serval Fact Sheet. San Diego Zoo Global Library <http://library.sandiegozoo.org/factsheets/serval/serval.html> downloaded on May 01, 2012

Schmalz-Peixoto, K.E. (2003) Factors affecting breeding in captive Carnivora. University of Oxford, Oxford. Unpublished thesis

Shepherdson, D.J., Carlstead, K., Mellen, J.D. & Seidensticker, J. (1993) The influence of food presentation on the behaviour of small cats in confined environments. Zoo Biology 12: 203-216

Skipper, G. (2011) Zoos SA Animal Management Policies and Procedures: Animal Transfers. Zoos SA, Australia

Sunquist, M. & Sunquist, F. (2002) Wild Cats of the World. University of Chicago Press, IL, USA. pp.143-151

UNEP-WCMC (2012). Serval. UNEP-WCMC Species Database: CITES-Listed Species <http://www.cites.org/eng/resources/species.html>

downloaded on 03 September 2012

Wackernagel, H. (1968) A note on breeding the serval cat, Felis serval, at Basle Zoo. International Zoo Yearbook, Vol. 8, no. 1, pp. 46-47

WAZA (2012) Serval. World Association of Zoos and Aquariums. <http://www.waza.org/en/zoo/visit_the_zoo/cats-1254385523/leptailurus-serval> downloaded on September 03, 2012

Weigl, R. (2005) Longevity of mammals in captivity; from the living collections of the world. Kleine Senckenberg-Reihe. Stuttgart, Germany

Wilson, D.E. & Mittermeier, R.A. eds. (2009) Handbook of The Mammasl of the World Vol. 1. Carnivores. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona.